It is important to draw the bullseye before throwing the darts.

moreClearly articulating how climate-related decisions will be assessed before starting to evaluate the data will provide a more objective evaluation, more quickly. It can also help in deciding the best approach (e.g., the level of detail needed) and guide model selection. All together, this will help insure the climate change information is fit for purpose in that the information obtained is appropriate for the questions that are being asked of it.

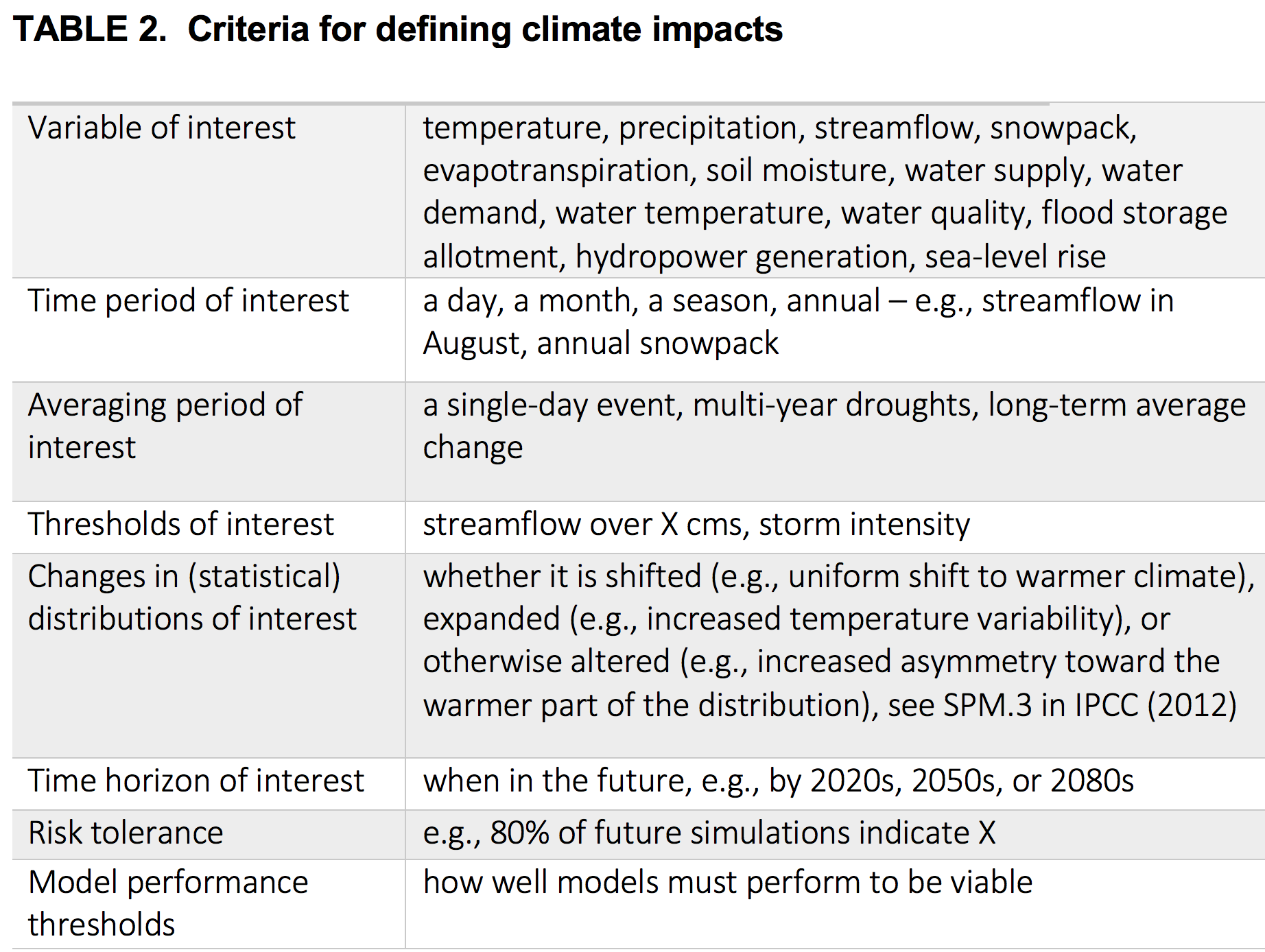

Learn more about: level of detail needed ; forthcoming DO on how better defining the decision helps guide model selectionEvaluations can include a variety of criteria (Table 2, see below). Being specific about the criteria helps to define an approach and determine whether the change is significant, i.e., how big of a change matters and with what degree of confidence. Rarely, however, is there just a single concern and decision makers must prioritize (Palmer et al. 1999). This list provides examples; additional water-related climate impacts can be found in past guidance (e.g., EPA and CWDR 2011, Box 4-1) and an overview of a range of hydroclimate metrics and their relative ability to characterize hydrologic changes can be found in Ekström et al. (2018).

The general idea is that models should be used that have appropriate capabilities and can be evaluated based on those capabilities to show they adequately represent the variable(s) of interest. The National Research Council (NRC) report on advancing climate models (2012a) shows the time scale and spatial extent for key climate phenomena and the relative climate model reliability. Most water resource impacts involve processes that occur at a local scale and thus require downscaling of the climate model outputs and the application of hydrologic models. For example, if floods are the focus, the downscaling method should adequately capture flood-generating precipitation events and the hydrology model should adequately represent peak flows in current climate, and the processes that could lead to flooding in a future climate (e.g., rain on snow).

Knowing the variables of interest can help determine the climate variables and models needed to simulate changes – for example, streamflow estimates require more climate variables (e.g., daily temperatures, precipitation, wind speed) than temperature changes alone (Reclamation 2014a). Hydropower assessments will require consideration of reservoirs (e.g., Hamlet et al. 2010; Kao et al. 2015); sea-level rise and streamflow estimates require completely different approaches, although in some places both are required (Hamman et al. 2016).

Knowing the planning horizon can help determine the approach. For shorter periods (e.g., 20 years into the future), the various greenhouse gas emission scenarios will be more similar and a qualitative analysis and literature review might be adequate (Reclamation 2014a).

Learn more about: evaluating model capabilities ; forthcoming DO on how better defining the decision helps guide model selectionA first step in assessing impacts should be to define the climate-dependent decisions and consider the type of changes that would cause concern. Evaluation criteria in Table 2 below can help inform those discussions.