Chapter 2: Climate and Water Availability Assessments

2.1 Water-Availability Assessments

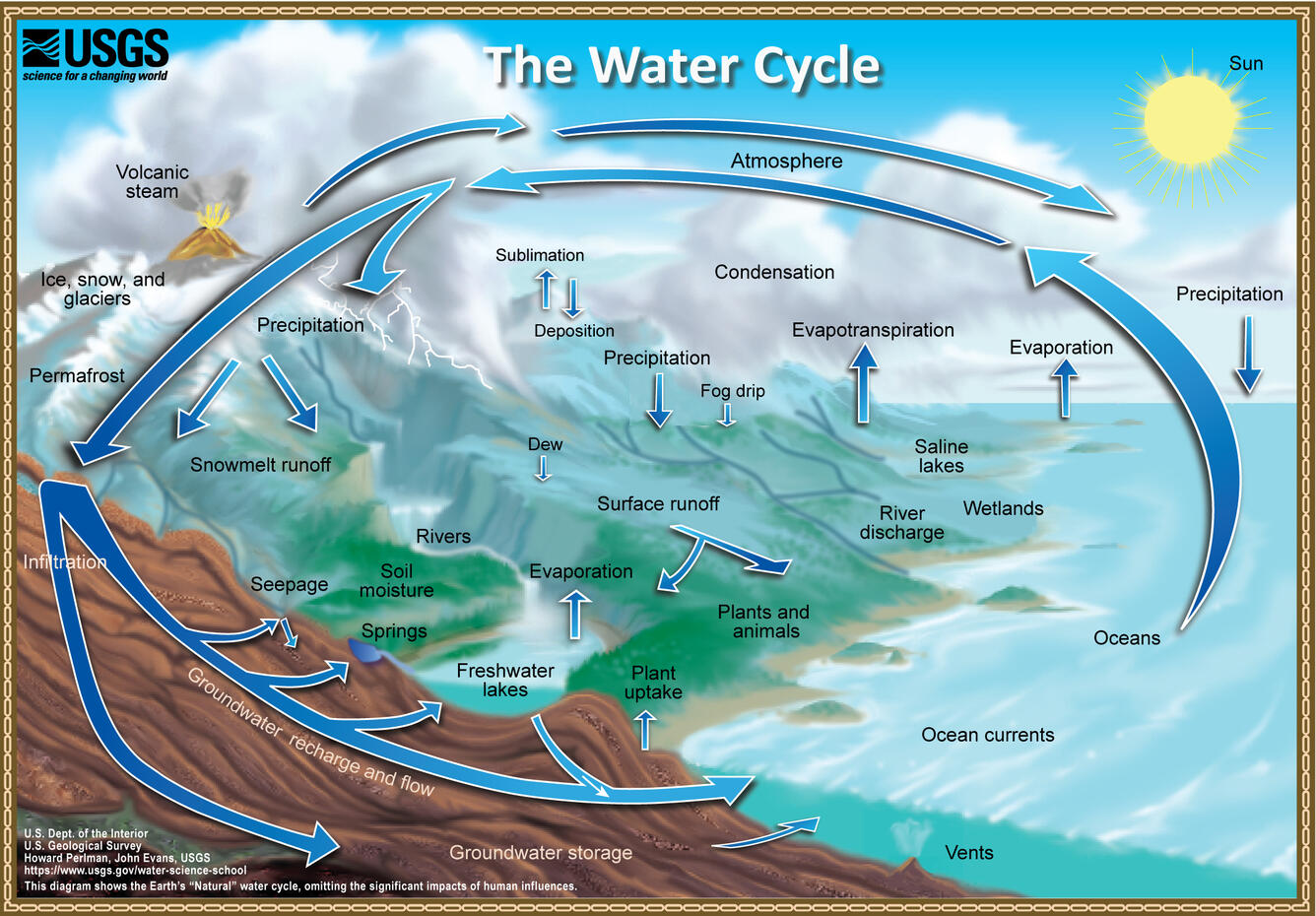

Understanding which climate elements are important to water availability assessments help us focus our efforts when performing climate-change impact studies. Climate changes, particularly changes in temperature and precipitation, have a direct impact on two key elements of the hydrologic cycle: evaporation and precipitation. Other elements of the hydrologic cycle—snowmelt, runoff, streamflow, and storage—are consequently influenced. It is also important to understand other, non-climate-related attributes of climate change scenarios (e.g. socio-economic projections, land-use change assumptions, etc.) that will affect water availability. While this climate primer will only cover attributes and the use of the climate-change scenarios, it is also important to mention that projected changes in elements outside climate change scenarios, such as changes in water management systems (e.g. diversions, storage, demand side management) will also impact future water availability. These are often evaluated in Integrated Assessment Models.

Perlman, Howard and Evans, John. The Natural Water Cycle (JPG). USGS. https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/natural-water-cycle-jpg OCTOBER 16, 2019

2.2 What is needed for science and research support

Note: This following section is summarized from COMET MetEd’s Climate and Water Resource Management Part 2

2.2.1 Define the problem/objective

When any scientific research is tasked to consider climate change, the starting point is to ask: what is the central aim of the study? For example:

How often might water temperatures in streams be too dangerous for aquatic life in the 2050-2080 period?

Why might we fail to reach water-delivery targets in the 2070-2100 period?

What are the chances of dropping below reservoir low-pool levels for more than one consecutive year in the 2040-2070 period?

Each of these questions examines the impacts of a future climate on a system performance measure. Below are example measures for these questions. Water managers, scientific experts (e.g., aquatic biologists), and stakeholders are all good resources for defining these performance measures. The problem and performance measures should be defined early in the study to inform selection of the datasets and models that are optimal (in terms of resolutions, accuracies, uncertainties) for the problem and target metrics.

Research Question |

System Performance Measures |

|---|---|

How often might water temperatures in streams be too dangerous for aquatic life in the 2050-2080 period? |

Threshold maximum water temperature and threshold exposure duration |

Why might we fail to reach water delivery targets in the 2070-2100 period? |

Annual water delivery targets |

What are the chances of dropping below reservoir low-pool levels for more than one consecutive year in the 2040-2070 period? |

Reservoir low-pool threshold |

2.2.2 What is relevant, reliable, and practical?

Once you’ve defined your research questions and objectives, there are three primary questions to answer when scoping a study that involves integrating climate-change information:

What is relevant?

Identify which climate impacts and climate-derived data are important. The answer will likely vary depending on the research topic and specific decisions that need to be made.

What is reliable?

There are varying degrees of confidence in projected climate and climate-derived data. You must consider which set of climate projection data to rely on and which potential climate futures to consider.

What is practical?

The realities of the project, such as the availability of resources, time, and personnel.

The answers to these questions are closely related to the specifics of the project goals, location, and stakeholder needs, and can vary from project to project. You will need to balance the relevancy of the data and its reliability with the practicality of implementation.

What is relevant?

Simply stated, the “what is relevant” question asks you to identify which climate impacts and climate-derived data are most important. The answer will likely vary depending on the research topic and specific decisions that need to be made. When determining which data are relevant to a study, you should consider:

Climate data that describe potential future climate conditions pertinent to the study goals.

System performance measures that are most relevant.

For a given watershed, snowmelt may be more relevant to seasonal streamflow and groundwater recharge than rainfall. Therefore, projections of snowpack and snowmelt would be very useful.

Here are some of the data derived, at least in part, from temperature and precipitation projections:

Snow, snowpack, and seasonal snowmelt

Water demand (agricultural or municipal)

Potential evaporation and evapotranspiration

Streamflow (and streamflow extremes)

Severe drought

Severe flood

Sediment generation and transport

Water temperature

Water chemistry

Examples of relevant data for different studies

Relevant data for Reservoir Operations focused on the frequency of dropping below a particular reservoir pool elevation may include:

Precipitation

Temperature

Evaporation

Snow-water equivalent

Streamflow

Relevant data for long-term planning may include:

Temperature trends and the potential future range

Precipitation trends and the potential future range

Drought

Flood (both common and extreme)

Relevant data for species recovery and adaptive management may include:

Water quality (water temperature, water chemistry, sediment)

Temperature trends and the potential future range

Precipitation trends and the potential future range

Drought

Flood

Relevant data for infrastructure may include:

Flood (extreme)

Drought

Water-quality issues (water temperature, water chemistry, sediment)

What is reliable?

The “what is reliable” question recognizes there are varying degrees of confidence in projected climate and climate-derived data. To understand what is reliable, you should consider the following:

Balance reliability with relevancy

Consider time horizons for the study

Use historical observations to help determine reliability

You should consider which set of climate projection data to rely on and which potential climate futures to consider. Issues of reliability and uncertainty, and how they depend on time-horizon, spatial-scale, and means or extremes of a climate variable, are also discussed in Chapter 3 of this primer.

Given the inherent uncertainty in climate projections when considering climate futures, you may need to strike a balance between using climate data that are relevant and using data that are reliable enough for the purpose of your project. For example, highly uncertain data may be fine for a project exploring system vulnerabilities to potential climate-change scenarios, but may be far too unreliable to underpin an infrastructure investment.

Balancing Reliability With Relevancy

How do you determine which data are reliable enough to be trusted to answer the questions posed by the project? The challenge here is to determine how reliable the data need to be to consider it “reliable enough” for inclusion as potential future climate data.

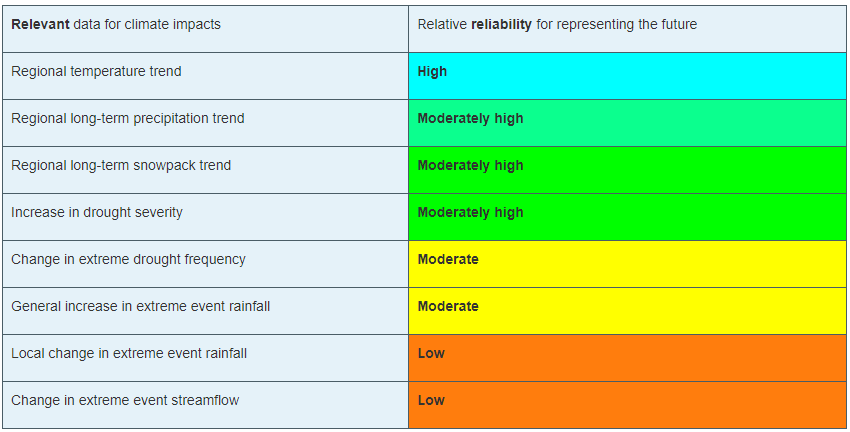

On a relative scale of reliability, average long-term temperature trends are the most reliable. In addition, many projects require future temperature-derived information, such as frequency of heat waves, seasonal snow, and potential evaporation. These are less reliable but still considered relatively reliable at representing potential future climate. The slightly lower rating is due to the need for more time- and space-specific information, and the influence of less reliably projected phenomena such as precipitation, wind, and cloudiness.

Precipitation projections are more uncertain, but may still be reasonably reliable on larger regional scales and for long-term averages. Depending on your research questions, objectives such as long-term planning, reservoir operations, and adaptive management may still benefit from precipitation data that are only moderately reliable for describing potential future climates.

For specific short-duration, local-area precipitation and precipitation-derived variables, precipitation-projection reliability is much lower. Yet these data are highly relevant to research questions related to extreme precipitation and runoff thresholds. Since extremes, by definition, occur rarely, you need to represent low-probability, high-consequence events in a future climate scenario.

Other approaches may help extract the most reliable possible information about local extremes, such as those related to the study time period and/or the use of historical observations.

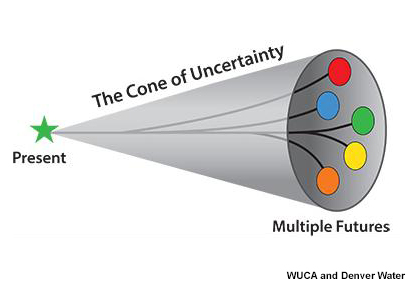

A study’s time horizon may help minimize some of the reliability issues when dealing with highly uncertain climate variables. Consider the cone below, where the lines and colored circles represent the hypothetical futures for five climate projections. The left side represents the current time, the right side 2100.

Historical observations may be used to increase our confidence in using variables with high uncertainty by providing context about the range of future conditions. This issue is also discussed in Chapter 3 of this primer. Historical observations fall into two categories:

Those from the period of instrumentation, which contains directly measured amounts and timing as well as trends

Paleo observations from ice cores, tree rings, alluvial deposits, or other proxy data, which provide estimates from before the period of instrumentation

The historical record of temperature, precipitation, snowfall, and other variables can be merged with projected trends to provide an estimate of the time sequencing of events, such as drought and flood, in potential future climates. Although the past is not a perfect predictor of the future sequencing of climate events, it may be the most reliable guidance for informing research questions that need that kind of information. An example of how this sequencing is carried out is provided in Chapter 5. This can be very important for objectives such as reservoir operations, long-term planning, and species recovery, where the regularity and frequency of events, like severe drought, are relevant and need the most reliable guidance.

What is practical?

The “what is practical” question is related to the realities of the project, such as the availability of resources, time, and personnel. Questions to consider include the following.

Do you have the necessary resources and modeling capabilities?

How might climate change affect your modeling approach?

Which climate-change influences can be represented practically?

Is it practical to expect that your study will sufficiently model system metrics? You may need to consider the following questions to answer that.

Are the models needed to incorporate climate change readily available?

How easy are they to run and how long do they take to run?

What are the implications of having to link multiple models, for example, a hydrological model that produces water temperature with a reservoir operations model?

The answers may determine whether the project has a good chance of successful completion.

Climate change itself may influence the choices you make for modeling and analyzing data for your study. For example, water temperature in a stream that has been historically controlled by groundwater input may need to be controlled by reservoir releases in the future. Such a study may require detailed information about the time evolution of variables as the climate changes. Model issues may pose constraints, making some approaches impractical given your project resources.

Is it practical to consider multiple futures given the following?

Resources and personnel available

Desire for project partners to explore the range of possibilities

Complexity and particular requirements for modeling the relevant influences

In some cases, using a small set of climate-change scenarios (such as a wet scenario and a dry scenario for long-term planning for water availability) may be the most practical approach for balancing multiple futures with limited resources. In this way, the study can explore a range of potential future climates with relatively low impacts on its resources. Chapter 5 of this primer will explore this issue further by providing an example of how this process is carried out.

2.2.3 Predictions vs. Projections vs. Scenarios vs. Storylines

As we look towards the future, there are different ways to estimate what it will look like. This section will provide a brief overview of the different terms such as forecasts, predictions, projections, scenarios, and narratives/storylines.

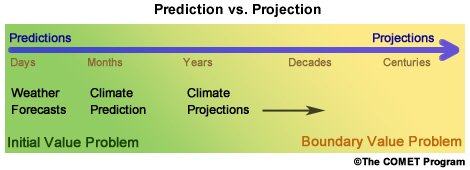

Predictions vs. Projections

Predictions and forecasts are probabilistic estimates of the future based on current conditions, with the expectation that decisions made today will have little impact on the estimates. Climate prediction refers to the short-term evolution of a weather system from an initial state under constant boundary conditions. The initial value is represented by the initial states of the climate system, including ocean heat content, and surface snow and ice cover. Predictions are associated with probability that can be verified. For lead times of weeks to months, predictions are typically based on both initial and boundary values. Climate predictions, such as seasonal outlooks, El Niño forecasts, and seasonal hurricane outlooks, fall into this category.

Projection refers to how the statistical measures associated with a climate system will change in response to changing boundary values. Climate projections are generally framed as “if-then” statements where decisions made today and in the future are expected to impact estimates. Projections, like predictions, may also be associated with probabilities, but they often cannot be verified in time to provide meaningful feedback to the climate modeling system.

Predictions and Forecasts |

Projections |

|

|---|---|---|

Short-term evolution from initial state with constant boundary conditions |

“If-then” statements, with changing statistics in response to changing boundary values |

|

Probability that can be verified |

Probability cannot be verified in time to provide meaningful feedback |

|

Examples: seasonal outlooks, El Niño forecasts, and seasonal hurricane outlooks |

Examples: end-of-century temperature increase range |

|

Scenarios

Scenarios are projections of what potential futures may look like. They require context and are generally used in pairs (e.g., with and without mitigation) or ensembles (e.g., the IPCC SSSP-RCP scenarios). There are several types of scenarios used in climate modeling, and many are linked.

“Climate-change scenario” describes a set of possible mean characteristics of a future climate; for example, hotter and wetter. Climate models are used to produce climate projections. Climate projections inform or provide the detailed climate information needed for climate-change scenarios.

“Emissions scenarios” represent realistic pathways of greenhouse gas concentration effects on the likely emissions rates caused by changes in anthropogenic factors. The emissions scenarios are the driving force, or cause; the climate-change scenarios capture the effect. Emissions scenarios are used as boundary-value input for climate models.

“Socioeconomic scenarios” represent societal drivers, including impacts from demographic, economic, and technological factors.

Narratives or Storylines

Shepherd et al. (2018) define storylines (or narratives) as “physically self-consistent unfolding of past events, or of plausible future events or pathways.” Storylines focus on understanding driving factors and impacts. They are useful when orienting towards stakeholder decision-making and policy, which are often driven by impactful events. Storylines are also useful for “bottom-up” approaches where you want to work backward from a particular event and “stress test” the system with compounding drivers (e.g., climate change and urbanization).

An example use of storylines for water-availability assessments is provided in Chapter 8

References: Shepherd, T.G., Boyd, E., Calel, R.A. et al. Storylines: an alternative approach to representing uncertainty in physical aspects of climate change. Climatic Change 151, 555–571 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2317-9