Chapter 7: Uncertainty

7.1 Sources of Uncertainty

Simulations of the climate system have multiple sources of uncertainty. Broadly, these sources are:

Model uncertainties

While most global climate models are built on the basic laws of physics, they vary in their levels of complexity in process representations, use of parameters for processes that are challenging to resolve, use of characterization datasets (e.g., land use/cover), grid and temporal resolutions, etc. For this reason multiple “physics-based” models will yield different solutions even with the same initial conditions and external forcings. Multiple models are often used to characterize this type of model uncertainty. While model ensembles are helpful, they may not cover the full range of model uncertainty. For example: the full range of structural uncertainties may not covered in typical multi-model exercises (e.g., CMIP); the models may not be entirely independent of each other; small spatial-scale features and long time-scale processes or tipping points are not fully represented (see: IPCC, 2021; Murphy et al., 2004; Masson and Knutti, 2011; Abramowitz et al., 2019)

Beyong model structural uncertainties, uncertainties can also be introduced to the model components through parameter estimation and initial conditions.

Scenario uncertainties

Future radiative forcing is uncertain due to unknown societal choices impacting future anthropogenic emissions, known as ‘scenario uncertainty’. The RCP and SSP scenarios used for climate projections aim to cover a range of possible future pathways but may not encompass all real-world outcomes. Additionally, there is uncertainty about the size and location of future large volcanic eruptions, the amplitude of changes in solar activity, thermonuclear war, technological change such as fusion, etc.. There are also uncertainties regarding past emissions and radiative forcings, which are crucial for simulating paleoclimate periods and the historical climate since 1850, and implicitly affect the development of earth system models designed to replicate these periods. Historical radiative forcings from anthropogenic and natural aerosols are less well constrained than those from greenhouse gasses.

Internal variability

Even without anthropogenic radiative forcing, projecting future climate involves uncertainty due to unpredictable natural factors like solar activity variations and volcanic eruptions (typically not considered in future climate projections), and on longer time scales, orbital effects and plate tectonics. Additionally, Earth’s climate experiences internal variations, such as those from modes of variability like ENSO, Pacific Decadal Variability (PDV), and Atlantic Multi-decadal Variability (AMV). These internal fluctuations, which occur over days to decades or longer, are unpredictable beyond a few years and contribute to the uncertainty in regional climate projections for specific decades (IPCC, 2021).

Interactions between radiative forcings and climate variations are plausible, such as influencing the phasing or amplitude of internal or natural climate variability. For instance, the timing of volcanic eruptions may affect Atlantic Multi-decadal Variability and ENSO; and additionally, anthropogenic aerosols may impact decadal modes of variability in the Pacific (IPCC, 2021; Zanchettin, 2017; Otterå et al., 2010; Birkel et al., 2018; Maher et al., 2015; Khodri et al., 2017; Zuo et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2016).

7.2 Ensembles

Ensembles of climate simulations, such as those from CMIP6, help explore and estimate these uncertainties. In this context, “ensembles” refer to a collection of multiple climate model simulations used to represent the range of possible future climate conditions, with the spread of these ensembles intended to represent this range. There are different types of ensembles, depending on the various sources of uncertainty in climate projections, including: Multi-model ensembles (MMEs): These include simulations from different climate models developed by various research groups around the world (e.g. CMIP). By comparing results from multiple models, scientists can better understand the range of potential outcomes and identify common patterns or discrepancies in climate response uncertainty. Initial-condition ensembles: These involve multiple simulations from the same model (SMILEs) with slightly different initial conditions (ICEs). This type of ensemble helps to capture the natural variability of the climate system. Perturbed parameter ensembles: These consist of simulations from a single climate model with varying parameters perturbed to reflect the full range of their uncertainty. This helps in assessing the sensitivity and thus uncertainty of a single model’s simulations. Using ensembles allows researchers to provide more robust climate projections by averaging across multiple simulations while also quantifying the uncertainty and variability in future climate predictions.

7.3 Uncertainty Quantification

For climate model projections, it is possible to roughly quantify the relative impact of various sources of uncertainty (e.g., Hawkins and Sutton, 2009; Lehner et al., 2020). Different climate models are used to estimate model response uncertainty for a specific emissions pathway, and multiple pathways are used to assess scenario uncertainty. The unforced component of internal variability can be estimated from individual ensemble members of the same climate model (e.g., Deser et al., 2012; Maher et al., 2019).

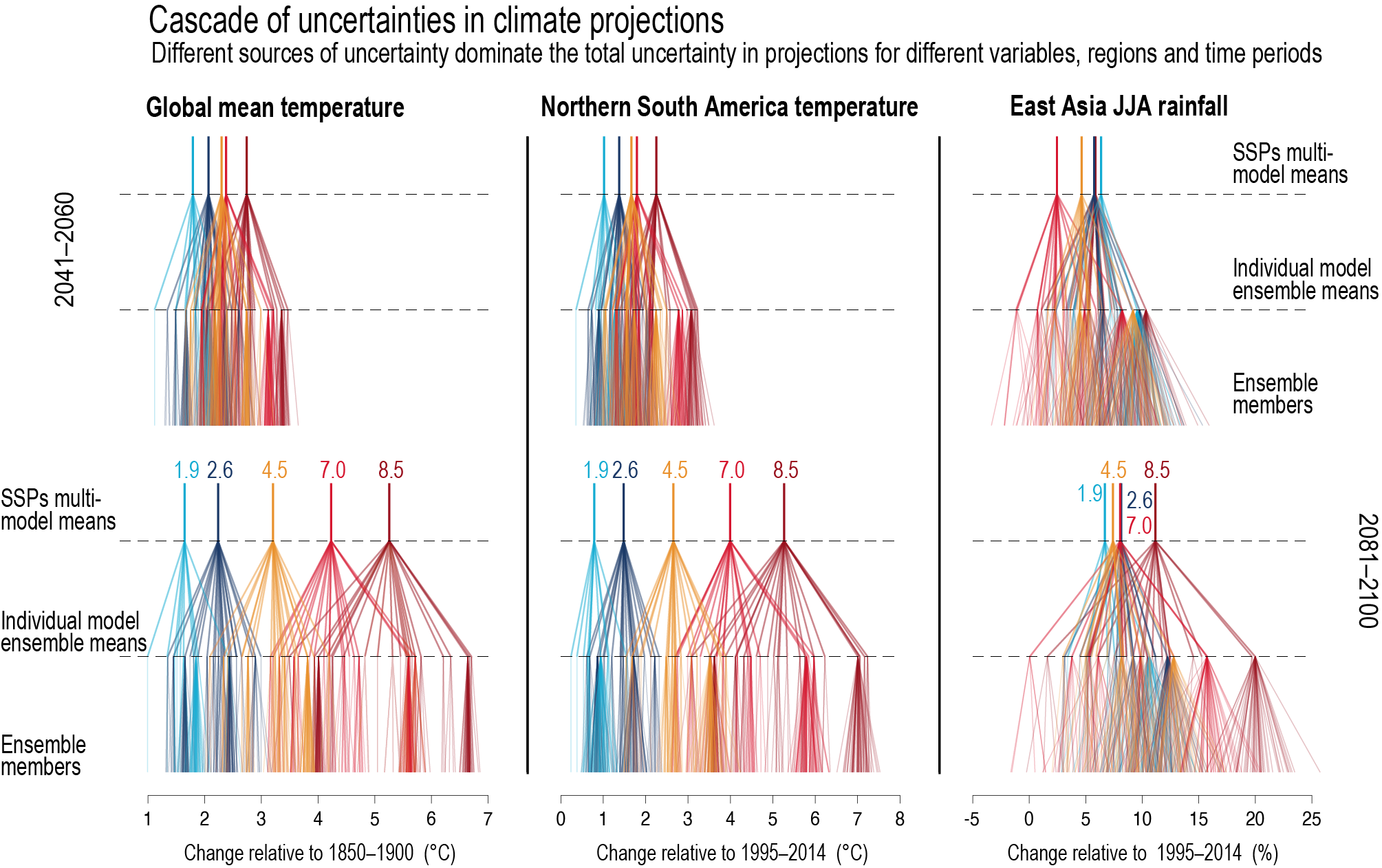

The figure below illustrates the relative size of these different uncertainty components using a ‘cascade of uncertainty’ (Wilby and Dessai, 2010), with examples shown for global mean temperature, Northern South American annual temperatures and East Asian summer precipitation changes. For global mean temperature, the role of internal variability is small, and the total uncertainty is dominated by emissions scenario and model response uncertainties. Note that there is considerable overlap between individual simulations for different emissions scenarios, even for the mid-term (2041–2060). For example, the slowest-warming simulation for SSP5-8.5 produces less mid-term warming than the fastest-warming simulation for SSP1-1.9. For the long term, emissions scenario uncertainty becomes dominant. The relative uncertainty due to internal variability and model uncertainty increases for smaller spatial scales. In the regional example shown in this figure for changes in temperature, the same scenario and model combination has produced two simulations which differ by 1°C in their projected 2081–2100 averages due solely to internal climate variability. For regional precipitation changes, emissions scenario uncertainty is often small relative to model response uncertainty. In the example shown in this figure, the SSPs overlap considerably, but SSP1-1.9 shows the largest precipitation change in the near term, even though global mean temperature warms the least; this is due to differences between regional aerosol emissions projected in this and other scenarios (IPCC, 2021; Wilcox et al., 2020).

Figure 1: The ‘cascade of uncertainties’ in CMIP6 projections. Changes in: global surface air temperature (left); Northern South America temperature (middle); and East Asia summer (June–July–August, JJA) precipitation (right). These are shown for two time periods: 2041–2060 (top) and 2081–2100 (bottom). The SSP–radiative forcing combination is indicated at the top of each cascade at the value of the multi-model mean for each scenario. This branches downwards to show the ensemble mean for each model, and further branches into the individual ensemble members, although often only a single member is available. These diagrams highlight the relative importance of different sources of uncertainty in climate projections, which varies for different time periods, regions and climate variables. (Figure 1.15 in IPCC, 2021).

More generally, the relative magnitude of model uncertainty and internal variability depends on the time horizon of the projection, location, spatial and temporal aggregation, variable, and signal strength (Rowell, 2012; Fischer et al., 2013; Deser et al., 2014; Saffioti et al., 2017; Kirchmeier-Young et al., 2019). The relative contribution of internal variability is larger for short than for long projection horizons (Marotzke and Forster, 2015; Lehner et al., 2020; Maher et al., 2021), larger for high latitudes than for low latitudes, larger for land than for ocean variables, larger at station level than for continental or global means, larger for annual maxima/minima than for multi-decadal means, larger for dynamic quantities (and, by implication, precipitation) than for temperature (IPCC, 2021; Fischer et al., 2014).